Most of history, just like life experience, is banal. When studying the past one must not forget this. The problem, when studying the lives of perpetrators or victims of WWII is that their lives culminated in part of an event that defines them. This has the effect of historical dehumanization. This is the use of the dead for purpose. The creation of historical narratives depends on this process. The goal when examining the past in the present is awareness. One must be aware of the use of one-sided personal histories to fill a need or agenda in the creation of a cultural memory. The same may be said for the creation of national or cultural identities. The history of the nation becomes defined by major historical events, usually containing mass trauma or radical change. This experience of the sublime is used to create memory. The banality is lost, as is identification with the real lives of the humans involved, who now become characters in the story of national, cultural, or class struggle. This is a defense mechanism to help make sense of a traumatic experience. Another effect of this process is the formulation of a new identity to replace the old. Austria chose the defense mechanism of forgetting or ignoring. When this proved too difficult a task, they chose the narrative of victimization. What are the effects of this? What identity formed around this? And what are the effects of the reversal of that narrative on the current cultural memory? Confused identity. The death of most participants in WWII before extensive research could be performed. A gap in memory. Current attempts at filling that gap carried out with sparsely informed memory creating a one-sided memory that is not full in its scope.

Judgement of dead generations is another form of distancing (like forgetting or ignoring or false narrative.) The accused were already judged or died before judgement. So now the best way to separate oneself and ones identity is to sit in judgement. This does not aid understanding. The memory must not only be “remember what they did or what happened to them,” but also “remember who they were,” this is how to explode the past in the present. This memory can be used as a way to form a new identity to replace the one formed by false narrative or active forgetting. “Remember who they were” leads to the understanding that humans experienced this and that experience can teach and serve as a warning. And by “they” it must mean all Austrians.

In some historical thought, one is warned not to judge individuals based on current moral standards. With the horrors of WWII this is next to impossible. Does one think of the horrific and murderous acts of past generals and leaders or is one to focus on their political achievements? For America this lends itself to narratives on slavery, genocide of the native Americans, various wars of conquest… All acts of atrocity and mass trauma. The debate over whether the Holocaust was unique is a difficult one. Personal stories and family histories are a tool used to understand some of these events, within the more overwhelming political narratives built around historical events. This humanizes the people involved and leads to the creation of a more accurate cultural memory. Rather than left or right wing political narratives that want the individual to remember something that fits their purposes. But how does a culture not judge by current moral standards? And shouldn’t there be judgement? If the current moral is that one should not kill, except when the government deems it necessary, (executions, war, economic sanctions,) then how is it different with current US soldiers etc? What about the fire bombing of Dresden and the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Acts of mass trauma on civilian populations based on ethnicity and/or race are not judged equally because the victors claim what is morally justifiable. The US also had internment camps. These are relegated to the side notes of history in most cases. Seen as history and not an active part of the cultural memory. This is why there are not memorials of shame in the US. It is a history Americans can distance themselves from through judgement if they subscribe to liberal narrative or they accept these acts as necessary to victory. (Which is how the Holocaust would have been treated by the German government if the Nazis had won WWII.) None of this debate lends itself to understanding unless there are attempts at memorialization (acts of commemoration or construction of memorials or education in public schools,) leading to little chance for contemplation or reflection on these events of mass trauma. Or, the current generations simply do not care. It is painful to think that “Grandpa, who I was always told was a hero, may not be, even though he was just following orders when he dropped those bombs on the civilian population of Dresden or Nagasaki.” It is similar to the memory debate in Austria, Austrians in the Wehrmacht were also just following German orders under victimization theory. To be told now that victimization theory is false is to be told one has grown up with a false memory. Americans cling to the accepted WWII narrative as they describe what it is to be American. Any discrepancy in the American narrative that has created the cultural memory is either utterly rejected or seen as “judging past participants in events of mass violence on civilians by current moral standards.” It is more accepted to examine the role of Americans in westward expansion during the 19th century because there is no emotional attachment. (And current American society has reaped the rewards of the Native American Genocide, so therefore entering into the “necessity” argument. Necessary for the land to be “civilized” by God’s people.) WWII acts of atrocity are very painful for the survivors, or children of Wehrmacht soldiers, because of the emotional attachment involved with loved ones. It is why victimization theory lasted so long. Its too close to home, too messy. The goal is to provide understanding and contemplation, not to provide a moralizing historical narrative. The difference between history and memory is crucial at this junction. Memory is the act of remembering the past in the present. History is the distancing of the past. “This is what is vs. this is what was.” The act of judgement is a current act done by using the morality one has come to live by. A society or individual institution cannot create an accurate judgmental or moralizing historical narrative because judgement (not in a negative sense, but the act of judging for oneself) is a present act. So it is in the realm of memory. One must have a well rounded and exhaustive set of research and facts, (based on humans not characters and more than one narrative) to contemplate and reflect upon to use to judge based on the cultural memory individualized. This includes the banality of human experience.

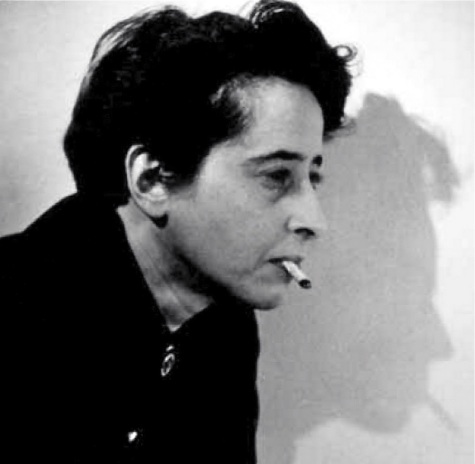

The act of Genocide, or supporting a genocidal regime goes against what has always been considered moral action. Crimes against humanity are a seperate category from the individualized act of murder. According to Hannah Arendt, this must be focused on when judging the actions of the individual, especially when it involves “acts of the state” or “superior orders.” Because if obedience to the state is seen as moral action, though the law and practice of the state violates basic human principles, (“We all know it is wrong to kill..etc.,”) then it is impossible to judge unless one separates the idea of a crime against humanity rather than an individual crime. This is how justice is served by the execution of Eichmann, though he was acting in accordance to laws defining and organizing a “moral” imperitive for the Third Reich. (Being that most laws are seen as being based in moral human principles, which is why they following the law is usually seen as a moral act.). Therefore to judge the individual for enforcing a law against humanity, based on a current moral standard is possible and necessary in crimes of such magnitude. The individual does have the ability to act against a criminal order or law. But making a judgement on political and individual responsibility in the present, using current moral standards, (and basic human principles and morals that have remained constant) still depends on cultural memory and the narratives involved because it is a present action.

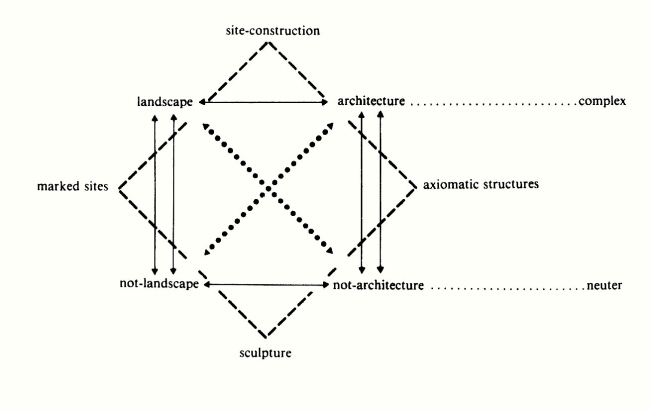

Arendt mentions the most poignant interview in the case of Eichmann being a story from a disposesed Jew who was helped by a Nazi Adolf Schmidt, (who was later executed for assisting multiple Jews hiding in the East.) She used this example to reinforce her opinion that “Every man deserves his day in court” to share his story or have his story told. This applies to the family history/research aspect of not only the anschluss, but the years that followed. It is time to apply this concept to the Flaktürme in Wien as well. Because the judgement inevitably is not one of individual responsibility at this point, (though each individual is responsible to act in according to basic moral standards, even in the face of totalitarianism,) the question is Austria’s POLITICAL RESPONSIBILITY. Because Austria has not responded to their dark past with the same measures as the German government. And six giant concrete examples of this are sitting in Wien, where the government is willing to sell them to private institutions or fence them off, but not use them as a base for research, contemplation, or reflection on what their presence actually means, (as opposed to the German historical research and memorialization process.). But there is the counter-argument that maybe the use or non-use of the Flaktürme emulates the progress those in power have actually made when attempting to come to terms with the past.

The purpose is not to create a case to afford justice. The purpose of studying the cultural memory and the Flakturms effect on it (as well as Anschluss memory) is to capture a phenomenon and to reflect on that phenomenon using many resources and multiple narratives. Then one may touch upon some of the reasons the Austrian identity formed the way it did, and reacts to the Flaktürme and Anschluss memory with such repression. Pointing fingers without an attempt at objective understanding is counterproductive. The goal is not to teach an obvious morality or to judge actions already deemed deplorable, (though the political responsibility question looms large,) the goal is to remember.

Scott Evans